A life without regret is one in which the soul has been allowed to express itself as often and as enduringly as possible. There are different dimensions of being: the body, the intellect, the emotions, and the soul. If you give too much importance to your body, you can only end up disappointed, especially at the twilight of your life, since the body withers until it finally disappears. Likewise, the intellect and the emotions have their limits, and it is difficult to truly flourish when relying solely on these two dimensions. In the end, what remains after your death is neither your body, nor your brain, nor your heart: it is your soul. It is therefore the soul that should have the final say. It is somewhat like when a war breaks out: those who decide are not the ones who die, or rarely so—namely the generals and the politicians, not the simple soldiers. Those who survive the conflict can reflect on the aftermath, but also on the before and the during. This example is somewhat paradoxical, for one might just as well argue that those who decide on wars should be the very ones who suffer their direct consequences—dying, in particular—and that such an “honor” should belong to the soldiers.

The Trap of Money

This question of the soul immediately calls to mind today’s model, which overvalues the pursuit of money and status, though both belong only to the material and social spheres. Money often conceals a desire to satisfy the body, the emotions, and sometimes the intellect. The soul, however, needs very little of the material world to be fulfilled. It is the content; the body is the container. A fine wine must be drunk in a clean glass above all; luxury is mere embellishment. Even if the glass were worth millions, it would not truly change the quality of the wine. To have the best possible tasting, one must focus on the content and simply ensure that the container does not alter the liquid with dirt or impurities. It is the same with the body and the soul. The soul does not need a body that has dined in the finest restaurants or slept in the most luxurious hotels. What matters is that it has eaten healthily, slept enough, and exercised—above all, breathed properly—in order to offer the best vessel for the soul’s blossoming. What matters next is to devote as much care as possible to one’s soul. On the scale of importance in tasting—that is, in quality of life—the winemaker, the spiritualist, is far more important than the sommelier or the wine merchant.

If money can solve many problems, it remains limited if one decides to be guided exclusively by the soul. This determination to focus on the essential explains why monks, for instance, take vows of poverty or chastity. To focus on the soul, one must learn to let go of certain things and preserve one’s energy to direct it in a single direction. Indeed, a corollary to the principle that nature abhors a vacuum is that if one fills one’s mind primarily with material concerns, it then becomes difficult to make room for more ethereal matters. Money, as it is often said, is a good servant but a bad master. To use it in pursuit of an honorable goal is difficult, for often, in trying to put it in our pocket, we end up putting it into our head and into our heart.

Do Not Take as Masters Those Who Have Not Yet Realized the Importance of the Soul

Whether in personal life or at work, it is important always to understand what motivates someone, especially when relationships of friendship or hierarchy are involved. A mercenary friend is like a worm in an apple: it is better to discard it. Likewise, working for people obsessed with money is problematic, for they will betray you sooner or later, as money always comes first for them. To their eyes, you are only a productive tool, and they do not consider you as having any value beyond that. You are a kind of product with an expiration date, a yogurt to be thrown away when deemed no longer useful. Learn quickly to know whom you are dealing with, lest you burn your wings at their contact.

The Soul First

To think with one’s soul, one must first acknowledge its existence and its primacy over the other dimensions of being. This recognition induces a form of spiritual education, whether acquired in childhood through the family environment, or later through books and online conferences. For the soul to have a place in our daily choices, it must be cultivated with habits. There is no secret: it is like the body, which needs regular activity, quality nutrition, restorative sleep, and deep breathing. As for the soul, a form of asceticism (fasting, meditation, etc.), or at least moderation in daily life, can help awaken it. Moreover, certain traditions indicate that the soul resides in the heart, and thus, thinking with the heart might be the best way to remain in harmony with one’s soul.

The Soul as a Solution to the Problems of the 21st Century

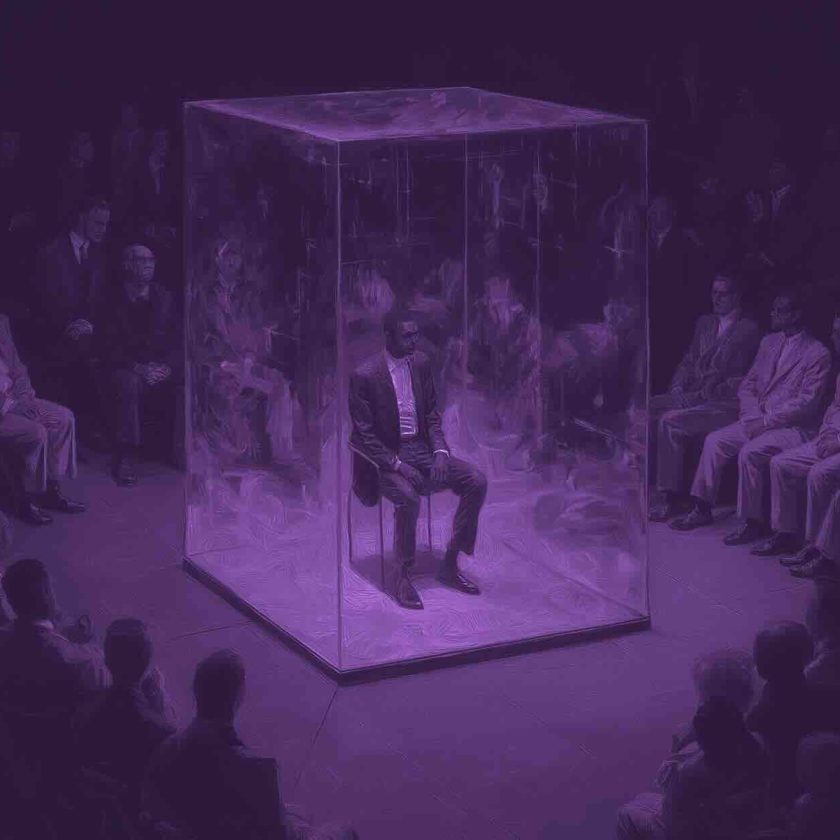

If the soul has so many merits, it is above all because it knows better—and earlier than others—how to solve all sorts of problems, especially those that involve morality and the long term. The “extra soul” one can display helps to grasp a problem in depth and to find a more adequate solution. Someone who lets their soul express itself more fully allows others to see what remains invisible to the majority.

To Go Further: Power or Service through the Guidance of the Soul – the Two Paths to Happiness –

The traditional model of society, based primarily on community, emphasizes contribution. In this perspective, mutual aid and participation constitute the very foundations of self-realization. By contrast, contemporary societies, born of industrialization, rest primarily on the individual and on their ability to access consumption, whether of goods or services. In this sense, these two models appear more antagonistic than complementary. Traditional societies, by definition older, have had more time to prove their worth. Industrial and post-industrial economies face a crisis that might be called civilizational. Since contribution to family or society is no longer truly valued, we already observe a crisis of birth rates in many places, though this is masked by immigration policies. The refusal to have children may, in some cases, be a sign of a quest for higher accomplishment; in others, however, it reflects an inability to conceive of the world outside the satisfaction of individual needs, rather than through the lens of contribution.

Power

The symbol of this quest for individual needs could be summed up in the will to power, which takes the form of the pursuit of hedonistic pleasures, the ultimate goal of which is money. If money is sought, it is primarily for the power it grants, notably its capacity to help us satisfy all kinds of pleasures. As organic beings, we develop from birth to death by trying to accumulate energy and transmit our DNA through reproduction. The fact of no longer truly feeling that we belong to a group, and thus no longer having to serve it, makes us less subject to natalist pressures. In earlier times, what made parenthood attractive—beyond the absence of contraception—was that the new generation could contribute to the group and support us in old age. The capacity to achieve economic success far from the original group (entrepreneurship, migration, etc.) renders obsolete the necessity of the generational duty (the act of engendering, of producing one’s likeness). Freed from this constraint, individuals lose more readily the sense of responsibility—once conferred by parenthood—and indulge more easily in the pursuit of vain pleasures, most often.